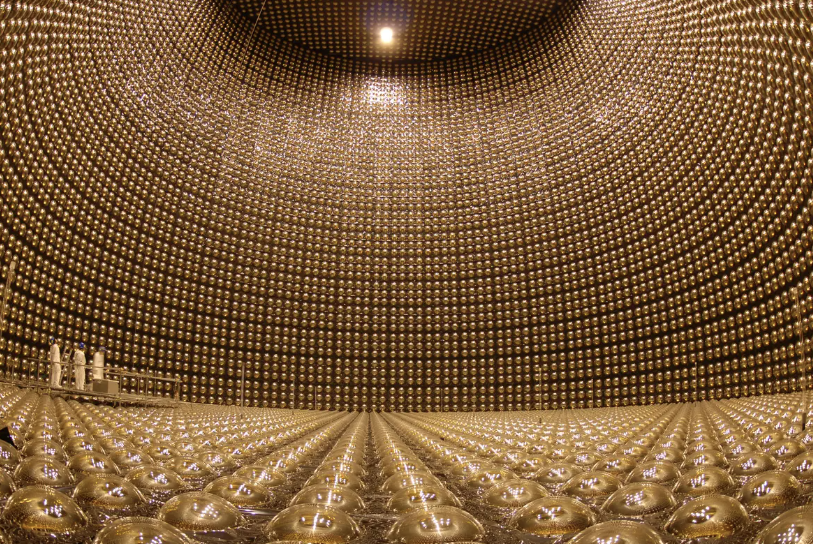

Last time, I clicked on a video for the only reason that it had a good miniature (yeah, I didn’t even look at the title). I was very surprised to discover the incredible Super-Kamiokande: an immense neutrino detector from Japan.

! When I finished writing this article, I realized it was a bit harder than the other one, as I’m not explaining everything (especially the beta decay part) because I wanted to go deeper into explanations!

Super-Kamiokande is located 1,000 meters underground in the Mozumi Mine, in Japan. It’s built this deep not for aesthetics (though the images are stunning and they made me click on the video), but to shield it from background noise, mostly cosmic rays that constantly bombard Earth’s surface. Even a single cosmic ray can generate a cascade of secondary particles that would totally drown out the tiny signal from a neutrino. The mountain acts like a natural filter, cutting out all that noise and leaving just the rare, clean signals we’re hunting for.

At its core, the detector is a massive cylindrical tank: 39 meters in diameter and 41 meters tall, filled with ultra-pure water. Not tap water. Not even “distilled” water. We’re talking water so pure it becomes chemically aggressive, absorbing ions from anything it touches. This is quite important because even the smallest contamination could cause false positives or interfere with the detection of the actual events.

Inside the tank, around 11 thousand photomultiplier tubes (PMTs) are mounted to the walls, pointing inward like a forest of light sensors. These PMTs are basically very sensitive eyes that can detect even a single photon of light. When a neutrino interacts with a water molecule (which is already very rare), it typically does so via charged current interactions.

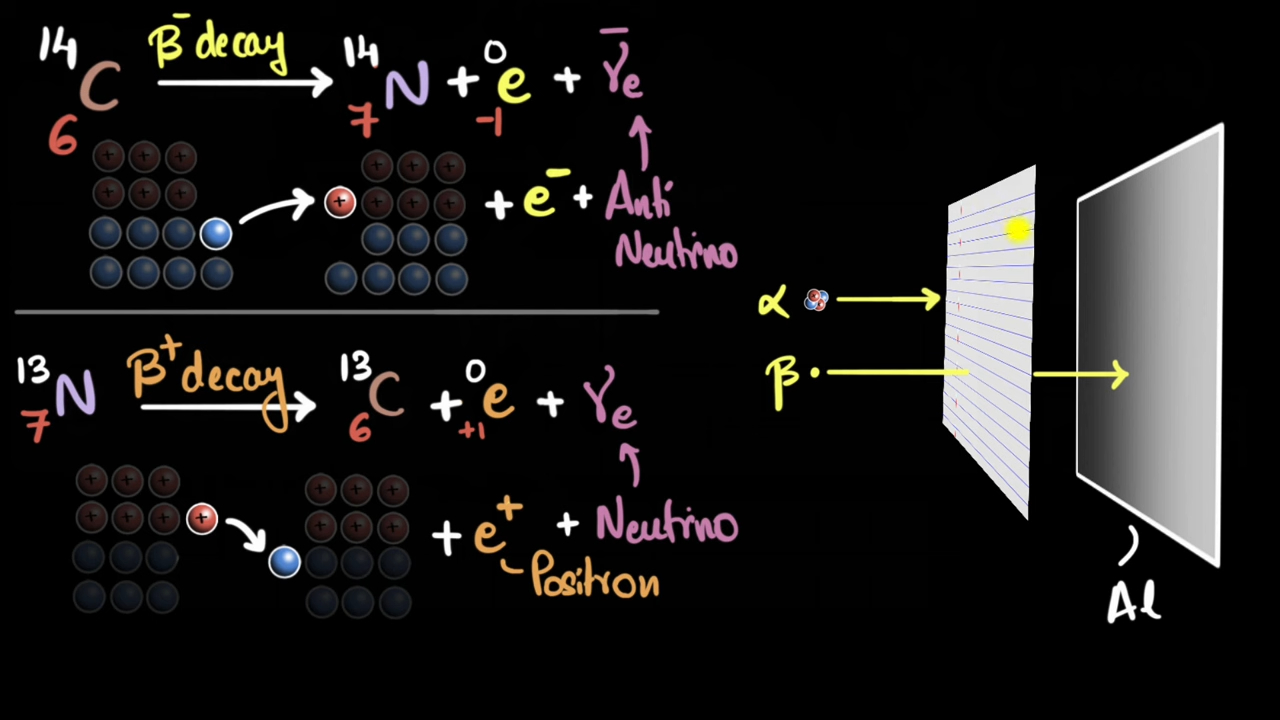

Charged current interaction is one of the most iconic examples: inverse beta decay:

ν̅e + p → e+ + n

An anti-electron-neutrino (ν̅e), sort of a ghost-like particle flying in from somewhere, maybe a nuclear reaction in the Sun or a supernova from millions of light-years away, enters the detector and hits a proton in the water. That proton is just part of a hydrogen atom (since water is H₂O, there’s tons of hydrogen available here).

When the ν̅e collides with the proton, something rare and special happens: they interact via the weak nuclear force (one of the four fundamental forces in physics), and the result is two new particles:

A positron (e+), which is the antimatter twin of the electron, and a neutron (n).

This positron is the star of the show. It’s moving fast, like faster than the speed of light in water. This creates a shockwave, not a sound shockwave, but a LIGHT shockwave. This is called Cherenkov radiation.

Important side note: it’s not actually breaking Einstein’s rule. The positron isn’t going faster than light in a vacuum (which is the universal speed limit); it’s just moving faster than light can travel in water, which is slower because of the medium.

Cherenkov radiation appears as a cone of blue light, and when this cone expands through the water, it eventually hits the walls of the detector. There, it smacks into the photomultiplier tubes (PMTs), which are basically ultra-sensitive light detectors.

The PMTs pick up this faint flash and, by analyzing the timing of the light hits, the pattern and shape of the ring they make on the walls, and the intensity, scientists can figure out all kinds of things: how much energy the neutrino had, where it came from, and even what kind of neutrino it was. The shape of the ring tells us whether it was from a positron or a muon, and the angle tells us the incoming direction of the original neutrino.

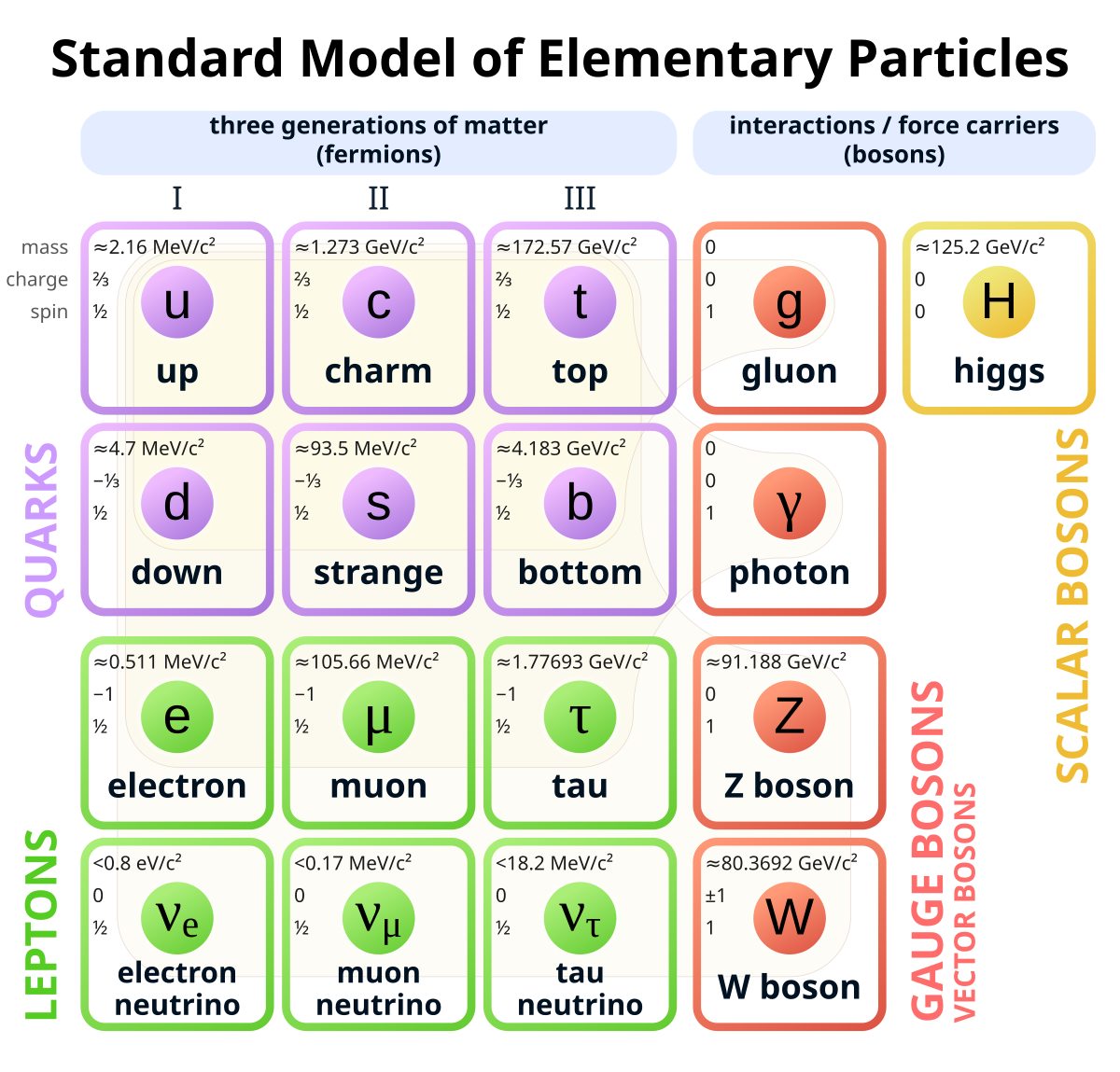

Now here’s where it gets crazy: there are three different types of neutrinos: electron, muon, and tau, and they can oscillate as they travel through space or matter. This phenomenon only makes sense if neutrinos have mass, even if it’s insanely small. Super-Kamiokande revealed that the neutrino actually has mass. At the time, this really shattered part of the Standard Model, because neutrinos having mass wasn’t originally included.

There are other types of interactions too, like elastic scattering (which is useful for detecting solar neutrinos) or neutral current interactions. To be honest, I didn’t deepen my research on these, so sorry, but for next time :) .

Recently, Super-Kamiokande has been upgraded by doping the water with gadolinium sulfate, which drastically improves sensitivity for detecting supernova neutrinos and diffuse supernova background neutrinos (essentially the echo of all supernovae in the universe).

In the end, what Super-Kamiokande is doing is kind of incredible: it watches pure water in absolute stillness, waiting for one single photon of light to flash in the dark, and from that, it just tries to deduce—who knows what?

credits:

https://indico.slac.stanford.edu/event/371/contributions/1206/attachments/570/927/goldsack_skibdcnn_npml2020.pdf (just the first pages)

https://www-sk.icrr.u-tokyo.ac.jp/en/sk/about/5min (this one in particular)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=aSYL0MHMwog

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iGr6atucsBw&t=12s

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nkydJXigkRE